Welcome to the 103 who entered The Physicality since the last post! With that, we have blew past the 600-subscriber mark. Thank you to Valerie Estrina for her glowing recommendation! It really helped and is much appreciated. Join the 623 of those who are into learning about the real world here:

According to my calculations, about 25% of you work for yourself. Like me! We have so much in common. So, that’s why I gotta share Carry’s financial products built just for us entrepreneurs. We don’t need to go corporate for 401Ks and Roth IRAs now! Check it out here.

This is the most impactful company I’ve written about yet.

Honestly, I’ve been intimidated to write this one because of just how vast it is.

Uber is the world’s single largest source of work. Yes — 6.5 million people ride for Uber. The entire U.S. federal government employs less than half that, 2.95 million. Walmart only has 2.3 million employees worldwide. Amazon? 1.5 million.

It’s ubiquitous. We took Ubers 2.4 billion times last year. A company that began as a black car service has seeped itself into our lives so thoroughly that it has almost gone the way of electricity, water, and heat: taken for granted. MadeinTYO was not kidding when he eloquently said, “Uber f*cking everywhere.”

However, Uber’s success wasn’t a foregone conclusion. Given they were the single biggest loser before an IPO in history, many investors didn’t think the rideshare + food delivery company could become profitable. It was just too unwieldy. Steering this car around would require unprecedented effort. But steered it did. Just a handful of years later, Uber is in the green by $450 million. The day of publishing, the public markets rewarded them with an all-time high stock price.

A maneuver of this sort surely required “Good Strategy.” My LinkedIn followers know that “Good Strategy,” a multi-faceted concept minted by UCLA Professor Richard Rumelt, is my Roman Empire. One of the ways he describes Good Strategy is,

“...a cohesive response to an important challenge. It creates strength through the coherence of its design — focusing efforts to achieve a powerful competitive punch.”

Let’s begin with the important challenges Uber faced and then assess how much of its response packed a “competitive punch” all the way to profitability.

Today’s ride:

#DeleteUber

The Strategy Kernel

Diagnosis

Guiding Policy

Coherent Actions:

Become a Supply-Led Business

Fly Wheel Fly

Laying Siege

War is Changing

#DeleteUber

People forget but Uber was hitting every bump and pothole possible on the way to and through an IPO. It was truly a remarkable disaster. Lowlights: Uber employee Susan Fowler full sent the essay that ousted CEO Travis Kalanick and his crew for a horrendous culture. The #DeleteUber campaign caused hundreds of thousands of customers to leave the platform, giving market share to Lyft. Their valuation was slashed from $68 to $48 billion in the private markets. A splashy autonomous division was stopped in its tracks after a self-driving Uber killed a pedestrian named Elain Herzberg. They were in trouble with govys all over the world. New York City paused new Uber licenses. London was going to kick them out. Uber had to cease their move into China. Losses were steep at $3.8 billion, the fattest loss for a company before going public in history. Shortly after IPO in 2019… COVID happened. Ridership fell off a cliff.

Luckily, they had new CEO Dara Khosrowshahi at the helm. Counter to most Silicon Valley-esque CEOs, DK was a true operator who had a grasp on financial and operational fundamentals. He honed his skills both as the CFO of IAC and CEO of Expedia. On paper, he seemed like the perfect leader to clean up this Uber-sized mess. Execution reveals all.

The Strategy Kernel

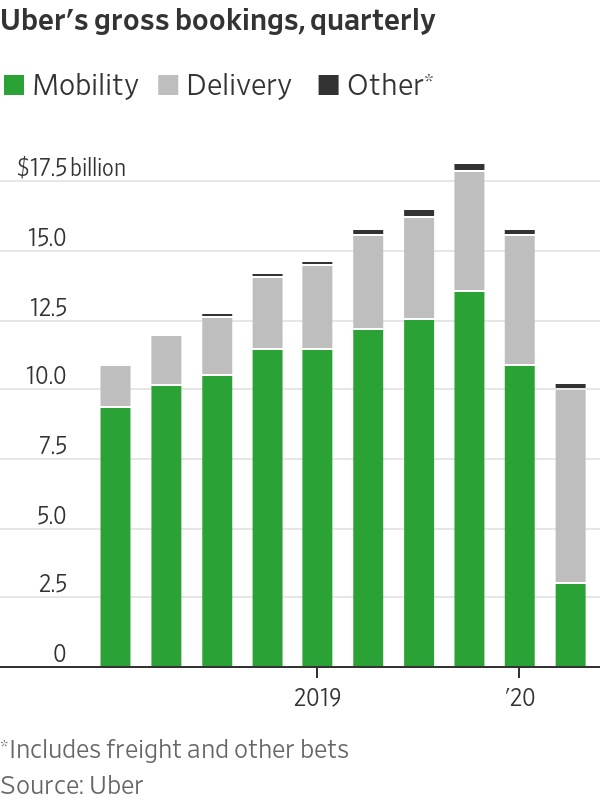

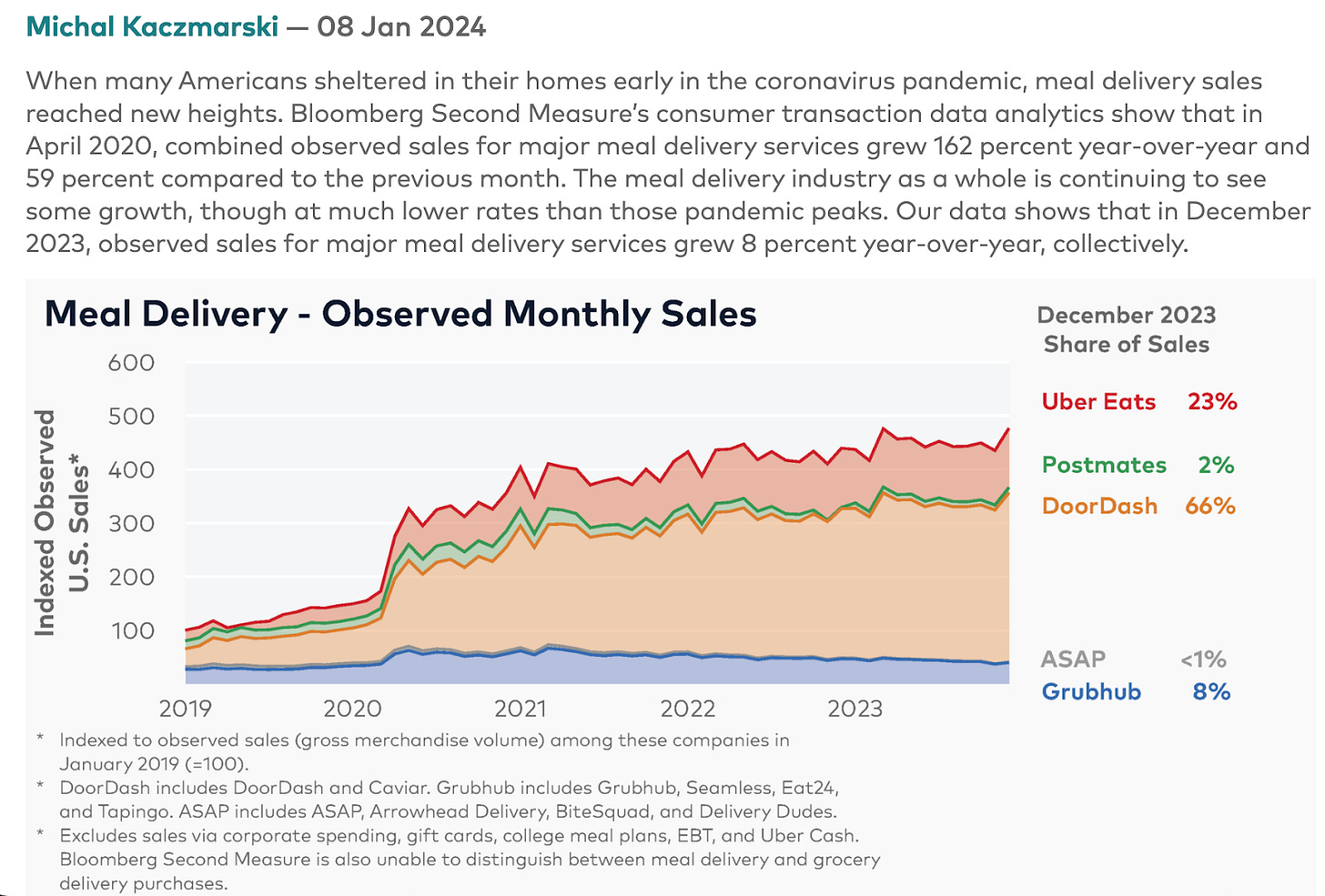

Uber has three main business lines. We are most familiar with Rides (~$5B in revenue) and Eats (~$3B in revenue). But they also have Freight (~$1B in revenue), a brokerage that connects truck-sized shipments with truck drivers. Each of these divisions are massive and competes with respectable peers in their respective categories. Their main domestic competition for Rides is Lyft, for Eats is DoorDash, and for Freight are legacy companies with old-sounding names like C.H. Robinson and J.B. Hunt.

Beyond these three pillars, Uber boasts dozens of partnerships across finance, travel, and hospitality including autonomous driving experiments with Waymo and eVTOL experiments with Joby. They offer different products, like Uber Moto, depending on the country. Uber even owns pieces of other companies like Grab and Lime. It’s all quite overwhelming.

To keep things simple, we’ll dial in on the strategies that turned Uber profitable. To do that, let’s look at Uber through the lens of the Strategy Kernel, a framework also created by Professor Rumelt. It consists of three parts: the diagnosis (what’s wrong), the guiding policy (how to fix it), and coherent actions (what we’ll do).

Diagnosis (What’s Wrong)

“A diagnosis explains the challenge. A good diagnosis simplifies the overwhelming complexity by identifying certain aspects of the situation as critical.”

When diagnosing Uber, it’s folly to claim the challenge was simply “costs are high” or “this business line is underperforming.” Those are symptoms of a problem. A doctor wouldn’t just list off “fever,” “aches,” “headache” – they would pack them up into a diagnosis: “cold.”

Before and through the IPO, Uber faced two main challenges:

The company is deeply unprofitable, primarily driven by high customer acquisition costs on both Rides and Eats. It was still a dogfight against Lyft and Doordash on every front: price wars, entering markets just to be in them, discounts, driver bonuses. It was hand-to-hand combat on the daily. The pressure was ratcheted up in 2019 when Lyft announced they were going to be profitable in two years. Uber had to figure out how to do the same. It was the millennial version of the Space Race – but you know, with much higher stakes for us.

The company has a horrible reputation with literally all of its stakeholders. No, I’m serious. Customers, drivers, investors, regulators, and employees all had beef. Uber even mentioned it in their S-1, “In 2017 our category position was significantly impacted by adverse publicity events.” Related, the board was a “catastrophe” (Dara’s words) that prevented the company from fixing major problems.

The second challenge was handled through a combination of what we’ll discuss below along with board and internal culture changes that are out of scope for this piece. With challenges identified, let’s get into the guiding policy — Uber’s approach to fixing it.

Guiding Policy (How To Fix It)

“An overall approach for overcoming the obstacles highlighted by the diagnosis. It channels action in certain directions without defining exactly what shall be done. A good guiding policy tackles the obstacles by creating or drawing upon sources of advantage.”

Uber’s single biggest advantage was that it was, and is, the biggest ridesharing company in the world. It was active in 700 cities at the time of IPO. This meant they accrued more drivers and riders globally than anyone else. It had incredible brand recognition in most major markets. It also had complementary, cash-flowing business lines serving the same customer base; something its competitors did not. In Lyft’s case, it was Eats. In DoorDash’s case, it was Rides.

With these advantages in mind, Dara’s guiding policies could have been:

Win drivers, because throwing money at customers has diminishing returns. Riders have zero switching costs between apps. They will use whichever is cheaper or will pick them up faster. Both of these variables are predicated on driver density. More drivers there are, the faster and cheaper pickups are. Drivers are the scarce resource to be coveted. While that seems logical now, it was not before.

Establish a flywheel that Lyft or Doordash cannot or will not replicate. Instead of fighting them head-on at their own games, change the game to one only they can play.

With the guiding policies established, it’s time for the doing. Coherent actions.

Coherent Actions (What We’ll Do)

“Coordinated policies, resource commitments, and actions designed to carry out the guiding policy.”

Coherent actions are what the company does to fix the problem, led by the guiding policy. These actions should sync up and feed into one another. I got three.

#1: Fly Wheel Fly

Your local Harvard MBA is no longer looking for “synergies.” They are looking for “flywheels,” an occurrence when different pieces of a business flow into one another, creating momentum that benefits the other. I joke, but if a business creates a true flywheel, it’s tremendously powerful. It rarely happens without extreme focus.

As Steve Jobs did when he took over Apple for the second time, Dara got to work on shrinking Uber’s product line. He sold their eVTOL platform to Joby Aviation, the autonomous division to Aurora, and scooters/bikes to Lime.

Of course, this immediately cut costs. But more importantly, it allowed Uber to operate like one machine versus a series of disconnected parts. Specifically, by letting Rides and Eats support one another. As the pandemic subsided and Eats started taking off on its own, Dara combined Rides and Eats into one team. In doing so, he consolidated the company into the supply of, and demand for, DRIVERS. This allowed for:

Driver Lock-In: A distinction between driving for Rides vs. Eats is that Eats has a lower barrier-to-entry. Drivers don’t need a background check nor do they need to get their vehicle inspected. The thinking here is that the faster Uber gets a gig worker earning money, the higher the chance they will buy into the ecosystem. So, they leverage Eats as a “structural recruitment advantage” (Dara) that its peers on both sides do not have. By offering earning options for all types of workers, it increases the overall supply in the marketplace. This, of course, has all types of advantages for us customers, like more consistent pricing and time-to-delivery/pick-up.

Cheap Advertising: Rides became the main customer acquisition funnel for Eats. They get more customers from Rides than they do from all other sources, including Google/Meta ads, combined. It's a proprietary and laughably cheap marketing channel.

Uber has expanded on this flywheel by evolving into a logistics business. If it needs to move, Uber wants to be involved: people, food, groceries, alcohol, packages — you name it. This change creates even more work for earners, further providing lock-in and attracting more drivers to the platform. This in turn makes the Uber ecosystem more viable for consumers. Flywheel in action.

Now, the part of the business that doesn’t seem to play nice with the others is Uber Freight. Yes, I know I just said Uber is becoming a logistics business. But the freight industry is a different beast entirely! Given that trucking requires a special license and is mostly done outside major cities, Uber likely can’t convert drivers from the other business lines into Freight. Additionally, they can’t cross-sell anything here. It doesn’t make sense to advertise a truckton of burritos to us when we’re buying a singular burrito. Freight doesn’t appear to benefit from the rest of the Uber ecosystem in the same way.

A friend at Uber explains that the perceived synergies are sneakily between Freight and Eats. For example, Starbucks is a Freight customer. Uber moves things for them. At the same time, Starbucks sells on Eats. So, the demand side of Freight can be the supply side of Eats. And then we, the end customer, buy from Starbucks via Eats. Uber is now part of the three major logistical steps for Starbucks. Distribution center to store. Store to customer.

It kind of makes sense? But it doesn’t seem to be as “cohesive” as the other parts of its strategy. The financials reflect that. In Q3 2023, Freight revenue was down 27%, for the fourth straight quarter of losses. Uber attributes this underperformance to the ongoing “consequence of the challenging freight market cycle,” which we’re certainly in. My Uber friend shares that Freight was profitable before “the greatest freight recession since 2008” and is confident it will be again. But, this is a piece about Uber’s climb to profitability. Freight could be an exciting growth driver for the company down the road but it isn’t helping the bottom line right now.

Outside of Freight, Uber has been diligent about choosing business lines where they don’t have to worry about diverting attention between growing supply and demand like their competitors on both sides do. The flywheel they’ve established with Rides/Eats moves both riders and drivers organically between businesses. I’m a prime example. I exclusively use Uber for both my food and ride needs because there are benefits to staying within the ecosystem. Now Uber can focus on the constrained resource that is drivers.

#2: Become a Supply-Led Business

Uber is a marketplace. It has drivers/earners (supply) on one side and riders/eaters (demand) on the other. Former CEO Travis Kalanick was all about demand and frankly, was probably making the right call in the earlier years. But just like riders, there is nothing stopping drivers from engaging with multiple companies. If drivers preferred Uber, riders would benefit from shorter pick-up times and expanded coverage. To get to the next phase, Uber re-oriented the company to become a supply-led business. Driver first. The coherent actions were:

Improve the Driver Experience: After years of investment on the customer side, Dara said on Acquired that they changed the company’s attitude towards serving drivers: “There's been a culture change of the company, which is a higher duty of care of how we build for earners.” To do so, Uber set up “180 Days of Change” to improve relationships with drivers and understand what they needed. This program yielded key changes like tipping, paid wait times, and app improvements.

Balanced the take rate: As the marketplace owner, Uber makes money from each pairing of supply and demand. Rides is a ~20% take rate business while Eats is ~30%. All Uber would have to do is increase the take rate just a little bit to add a ton more money to their bottom line. Sounds easy, right? Dara asserts,

“Our job is to grow [ride] volume as much as we can [while] minimizing the take rate, which is taking as much of that dollar and giving it to drivers. I can move my take rate up a little bit. But it's too easy. It's too tempting. We're very hardcore about like, no, no, we got to keep the take rate low.”

It’s perilous. Take any more away from drivers and they leave for greener pastures. Take any less and you’re harming your bottom line. Sticking to these take rates forces Uber to improve its profitability position in other ways.

While this supply-side focus has improved things, Uber’s relationship with drivers remains turbulent. A 2023 New York Times article shares multiple instances where drivers haven’t been able to make ends meet even when working full-time. After investing heavily in cars that meet Uber standards, they feel trapped in an endless cycle of insurance payments, cleanings, and repairs.

These feelings are substantiated by an analysis published in Forbes by Columbia University professor Len Sherman. He concluded that Uber’s recent profitability came from jacking up their effective take rate to ~40% through an under-the-hood change. He writes,

“Uber’s most recent pay cut [to drivers] was enabled by "upfront fares plus destination” (UFD). UFD decouples driver base pay from time and distance. Instead, AI sets upfront pay based on unspecified factors. Drivers have seconds to respond to trip offers, [fearing] that refusing too many trips may put them in a “penalty box” of unknown duration, ghosted from receiving additional offers.

When an Uber driver [refuses] an offer, other drivers are allowed to bid for the same trip, pitting drivers against each other in a race to the bottom for who will be first to accept a low-paying trip. By decoupling driver pay from actual trip time and distance, UFD gives Uber broad discretionary control over setting trip pay to the lowest level any driver is willing to accept. From the company’s perspective, why pay the previous rate-card guaranteed minimum fare if Uber can find a driver willing to accept lower pay?”

Sherman’s analysis is summarized in this graph here:

Sherman deduced that Uber’s average pay per trip declined by nearly 12% right around when UFD rolled out. In response, Uber denied this analysis stating,

“Uber's take rate is nowhere near 40%. The premise that Uber has achieved profitability by increasing the percentage of the total rider fare that it gets from drivers is fundamentally false.”

As with most things, the truth is likely somewhere in between. Regardless, Uber needed to stabilize the driver experience after years of neglect. Doing so when they did defended its market share from Lyft at a time of internal weakness. If Uber didn’t make the driver experience at least as good as Lyft’s, things could have gone real bad. At this point, it seems that the main draw for drivers to stay on Uber is demand volume. More riders are using Uber so it’s just quicker for drivers to get matches.

#3: Laying Siege

Uber is having the most trouble with dominating the food delivery business in the United States. They face their toughest competition here. So instead of fighting the same fight, they opted for a different approach. Dara reveals,

“We are focused [to] build profit pools outside of the U.S. [and] use that to attack the U.S. over time. Then use the structural advantage to gain category position against DoorDash.”

Leaning on their global brand, they doubled down abroad, which was already 15% of their Rides growth. To achieve this, they combined building with buying and partnering. To expand in the Middle East, they bought competitor Careem, who already had customers in Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates with a pathway to customers in Pakistan, Qatar, and Morocco.

To expand elsewhere, they changed their internal stance on how they enter markets. Dara says,

“The attitude [before] was, if our business model isn't legal, then we're not coming in. [Now], let's adjust our business model to the country versus have the country adjust to the business model. Once you're in, you build trust within a country, maybe then the business model can change over a period to benefit drivers, couriers, et cetera.”

Uber was famously anti-establishment. They were going against the taxi industry, after all. But in that process, they rubbed a ton of governments the wrong way. As opposed to his predecessor, Dara made sure to make nice with everybody. In his first few weeks, he saved Uber from being kicked out of London. Because of this tact, they’re now in places like Germany, Spain, Japan, and Korea. They’ve partnered with traditional taxis and more niche forms of travel like boat providers in Mykonos and London. This geographic reach is balanced by exiting markets they weren’t working out like China and Barcelona.

Dara will parlay Uber’s heft in Rides to profitably expand food delivery, using the flywheel mentioned above, outside the States. He will then use that cash flow to chip away at DoorDash’s leadership position here by using the same door-to-door growth tactics as before. The war is on.

War is Changing

It seems that, yes, Uber’s climb to profitability was indeed an example of Good Strategy. They lightened and focused the business to create a flywheel which allowed them to focus more on the driver-side of the marketplace which allowed them to build profit centers abroad to fight DoorDash domestically. Not all the pieces fit together cleanly, of course. Uber Freight remains a promising yet troublesome leg of the stool. Becoming a supply-led business hasn’t yielded adoration from drivers either. Yet, the pieces were cohesive enough to establish a Good Enough Strategy to become profitable.

Dara isn’t resting on his laurels thinking the war is done. Getting profitable was just the beginning. He knows he still faces formidable competition. He tells Acquired,

“Lyft is stronger than people give it credit for. The new CEO is making moves, he's super aggressive. I feel way better today than I did five years ago, but I wouldn't count them out. DoorDash is a tough competitor. We don't like them, but we respect them.”

At $1.15B in revenue, Lyft still owns 25% of the U.S. ridesharing market while Uber owns the rest. On the food delivery side, DoorDash’s $2.2B in revenue commands a dominant 66% market share to Uber’s 23%. To compete domestically, Uber plans to work into the suburbs on both Rides and Eats — a geography type that is part of DoorDash’s profit pools.

Like a rebel group that only needs to win a few key battles to destabilize an empire, Lyft’s laser focus on ridesharing may eat into Uber’s largest business. As we laid out before, drivers are the precarious keyman (keymen?) risk to ridesharing. If Uber is not careful, the gaps they are leaving open in the areas of driver satisfaction may be Lyft’s opportunity to gain share.

To stay ahead, Uber still experiments all the time. For example, Uber hasn’t given up on autonomous. Instead of going at it alone, they partnered with Waymo to ensure Uber has a presence in that innovation. Beginning across 180 miles in Phoenix, Uber customers will be able to book an autonomous Uber or receive a package in one soon.

Regardless of what the future holds for the company formerly known as UberCab, its ascent into profitability is a journey worth adding to the halls of great business learnings. The power of Good Strategy is something companies of all sizes should learn to appreciate. Ok, I’m off to tank my 4.7 Uber rating even further.

Thank you for reading! Thank you to Kaley, Jack and Julianna for editing.

What’s next?

Invites to the first Joust will be out real soon. Just waiting to secure sponsors. If you’re into playing games with interesting people in beautiful locales, make sure to sign up here. The reception has warmed my heart and I can’t wait to see where this goes.

If you liked this piece, check out the greatest mobility hits: Shinkansen, Joby, Aero.

Subscribers sharing on socials has proven to be the best way for this newsletter to grow. I would greatly appreciate it <3