This Bullet Train is Just a Faster Horse

The Shinkansen teaches us strategic lessons and cautionary tales

Welcome to the 60 who have entered The Physicality since the last issue. If you aren’t subscribed, join the 499 others who care about the real world here:

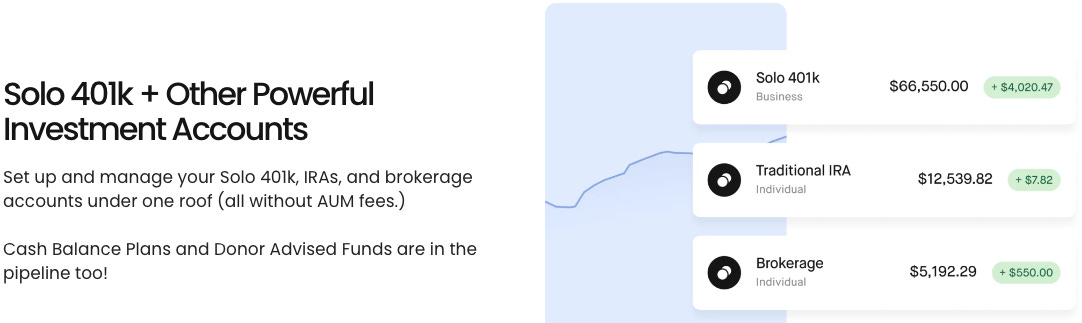

STOP IF YOU’RE AN ENTREPRENEUR/SELF-EMPLOYED LIKE ME

We’re the boss. We set the hours. But in exchange, we’ve had to give up retirement perks like 401Ks that come with working corporate. That’s why I’m hype that Carry made investment products for entrepreneurs. Now, I can easily set up their signature Solo401K or backdoor Roth IRA. Check it out here. Major unlock.

200 miles per hour.

1 million passengers a day.

Leaving every 3 minutes.

Delays measured in seconds.

In its 60 years, it has moved 10 billion passengers with no casualties.

When the Shinkansen, better known as the ‘bullet train,’ sped off in 1964, rail was already considered the past. Highways, not railways, were the future of cross-country movement. Planes, not trains, were the future of inter-city travel. Heck, rocket ships were taking off when Japan National Railways was laying down track. Compared to these breakthroughs, Japan’s insistence on high-speed rail looked like racing backward. Yet, they persisted. This single infrastructure project changed Japan inside and out.

The Shinkansen is still seen as a technological marvel, decades later. In its 60 years, only two other train lines compete with the Shinkansen for speed – France’s TGV and China’s HSR – but none compete for consistent experience and safety. Even by — no — especially by today’s standards, completing a project of this reach and magnitude in just five years is remarkable.

But it’s not all dreamy on the “Dream Super-Express.” The project was plagued by considerable political challenges and remains a source of financial struggle for Japan to this day. I wanted to look back on this mobility breakthrough to understand how the incredible gets made. What I found made me hit the emergency brakes. Strategic maneuvers. Cautionary tales. Inspiration. Deceit. Lessons we can apply to our own endeavors.

All aboard! Today’s stops:

The Dream Super-Express

Make a Faster Horse Mean Something

Detach the Cable Car

Reconsider The Win Condition

Build to Last Mindset

…But It Has to Pencil

Next Stop: Progress

The Dream Super-Express

Japan was at the precipice of rapid change when the Shinkansen plan surfaced. Jessamyn Abel explains in Dream Super-Express: A Cultural History of the World's First Bullet Train, the country was reinventing itself from a post-war recovery country into a kigyō shakai, an “enterprise society” in which “meeting the needs of the corporation is naturally congruent with meeting the needs of all society’s inhabitants” (Abel). Basically – Japan was down bad for capitalism.

And it was working. From 1940 to 1956, real per capita GDP blew past its prewar level. By the time the Shinkansen was built, Japan was almost right up with Britain and the USA.

The need for the Shinkansen began as deeply practical. The existing rail that connected the country’s two major commerce cities, Tokyo and Osaka, took seven hours. It was becoming a transportation bottleneck and limiter on Japan’s rapid economic growth. The Shinkansen would shrink travel time down to an astonishing three hours by:

Superior acceleration via electric motors to push individual rail cars, versus being pulled by an engine in front

Aerodynamism from the smooth bullet shape

Increased speed from not having to share a track with any other train

Increased speed from being on an elevated track with no railway crossings

Precision and efficiency with computerized trains with a central traffic control center in Tokyo

It took five years, from April 1959 to October 1964, for the Tokaido line — the original Tokyo to Osaka line — to be completed. It was a “320-mile line, consisting of 5,000-foot-long welded pieces of steel on a raised concrete, largely curveless track, [that] allowed the bullet-nosed trains to whiz through the countryside at speeds above 130 miles an hour” (New York Times).

The ride to get there was bumpy, however. Building the Shinkansen was not a foregone conclusion. It could have derailed at any time. There were divergences in route plans even as the project was underway. This was caused by grassroots pushback from citizens along the route and more nefarious campaigns to include track in places that did not necessarily need it. The scope creep, along with the burden of building 3,000 bridges and 67 tunnels, sometimes through mountains, led to cost overruns of 200 billion yen — twice the original estimate. Big yikes. More on that later.

When the Shinkansen debuted on national television in 1964, it was moving so fast that the news helicopters struggled to keep up. It made moving cars look like they were standing still. It inspired the world then as it does today. It now reaches every corner of the country. It has increased speed by ~60mph and decreased delay times to 12 seconds on average. Still no casualties.

Now, let’s unpack how the incredible got made and what it can teach us.

Make a Faster Horse Mean Something

For much of humanity, infrastructure was considered technology. Dams and bridges were seen as innovations akin to how we view the internet and smartphones today. Somewhere along the line, we have taken infrastructure for granted. We pay attention to it only when it’s not working. Perhaps this is natural. Or perhaps infrastructure projects can learn a lesson from how the Shinkansen hyped up an entire country.

“The world’s fastest train” wasn’t all that exciting when compared to planes, highways, and space flight. Domestically, new highways were allowing car and bus travel between cities. A new monorail connected Tokyo to the airport, making air travel more convenient. Given this booming travel apparatus, it could be argued that a faster train hardly seemed necessary. This was just a faster horse! On top of that, the Shinkansen wouldn’t impact most citizens' daily lives. So why was it made? By making a faster horse more than just a faster horse.

What began as a straightforward infrastructure project rapidly encapsulated so much more. Abel writes,

“The explanation for this seemingly incongruous national excitement about a high-speed railroad lies not in some universal enthusiasm for three-hour trips between Tokyo and Osaka, but in the power exerted by the very idea of a fast, high-design, high-technology transportation infrastructure… infrastructure that would showcase Japan’s economic and industrial potential to the world.”

The Shinkansen was re-marketed from an improvement project to a source of national pride. It became a diplomatic lever. During construction, it was regularly shown off to domestic and international leadership. It launched just in time for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics when flocks of foreigners were visiting. This spotlight was critical as the country was reintroducing itself to the world.

The Shinkansen was presented with a gravitas that encapsulated Japan’s collective desires, hopes, and dreams. Abel continues,

“[Shinkansen’s] importance came from the ways it prompted the reimagination of identity on the levels of individual, city, and nation in a changing Japan. The bullet train was built to move people at high speeds from one city to another, but it also moved people’s hearts and minds: it conveyed meanings, instilled feelings, and evoked emotional responses.”

This reminds me of the recent 12-day reconstruction of the Interstate 95 highway in Pennsylvania. As reported by Packy McCormick in How to Fix a Country in 12 Days, Governor Josh Shapiro, “turned an infrastructure project into a sporting event. It live-streamed construction. It made heroes of tradespeople. It was a great first step, and a hint of the way we should build things in this country: as a competitive sport for which people feel as much local pride as they do for their football or basketball teams.”

We can take a page from the Shinkansen playbook and find ways to awe with the otherwise mundane. Not everything has to be “cutting-edge”. Sometimes, you just need to hype up a faster horse.

Detach the Cable Car

Japanese National Rail President Shinji Sogō was the Shinkansen’s patron. He willed the train into existence through a combination of clever political maneuvering and outright deceit.

Sogō knew the odds were against him. Like with many infrastructure projects, getting started isn’t necessarily the hard part; finishing it is. To ensure the government stayed committed, Sogō secured a $80M loan from the World Bank. This loan meant that Japan was telling dozens of countries that this bullet train would be completed. Given that Japan was eagerly establishing post-war ties with many member countries, the pressure was ratcheted up that much more.

This loan was designed not to exceed 15% of the 200 billion yen cost of the project. That, as we mentioned before, was not the case. It turns out that Sogō kept cost estimates deliberately low. He feared that if he shared the true figures, neither the government nor the World Bank would back his bonkers idea.

After the egregious cost creep came to light toward the end of the project, he resigned. As we’ll show later, these overruns weren’t just his fault. He was later awarded the “Grand Cordon of the Order of the Sacred Treasure” by Emperor Hirohito for his extraordinary service to Japan.

I am not condoning fraud. I highlight Sogō’s approach because he found a way to “burn the boat”/”detach the cable car.” He didn’t give his government any other option than to complete the project in a timely fashion. Find a way to take failure off the table.

Reconsider The Win Condition

Kyoto is the cultural center of Japan. It maintains traditional architecture, is home to 17 UNESCO World Heritage sites, and is a great place to experience cherry blossom season. Given how vital this city is to tourism, it seems ludicrous that its future along the Shinkansen was contentious almost until the track’s completion.

There were myriad reasons for this:

Kyoto’s split government — two opposing parties simultaneously in control of the project — made internal cooperation difficult.

The city made tough demands on JNR including that the train org cover all construction and citizen relocation costs.

Kyoto was reluctant to facilitate the needed land purchases to make the stop a reality.

But these were all solvable issues. Turns out that after years of debate, the real reason that JNR pushed back against adding a Kyoto stop was that it would break their promise of “Tokyo to Osaka in three hours”... by up to five minutes.

It seems that along the way, JNR lost the plot. The entire goal of the Shinkansen was to connect cities faster than before to generate economic growth. How quickly the train moved was secondary. “Unless the line was useful to passengers, speed alone was meaningless” (Abel). Eventually, JNR acquiesced and Kyoto was included on the line. All that fuss slowed down the project and generated needless confusion.

Periodically re-explore your win condition before a guidepost becomes a jail cell. Be open-minded when pairing that win condition (move people) to a metric (three hours). Don’t be married to the metric for the metric’s sake.

Build-to-Last Mindset

The Shinkansen was completed in five years. 300+ miles of track. A novel combination of civil engineering and computers. That’s remarkable enough on its own. But what is even more remarkable is that it wasn’t done haphazardly. It was built to last.

As said before, speed was never the primary objective. It could have gone faster. The project precisely balanced train speed with safety, passenger comfort, and most importantly, consistency. They designed the line to withstand 60+ trains running every day. They optimized every detail to prevent delays or pausing service for maintenance. JNR built for longevity.

Since it was created, speeds have only increased from 135 to 200 mph. Delays have decreased to 12 seconds on average. In their rigorous pursuit of perfection, they have made improvements to their tracks, their computers, and the shape of the train itself all the while adding more stops. It wasn’t flash-in-the-pan greatness. It was the ongoing pursuit of perfection without cutting corners.

We’ve known what it would take to replicate the Shinkansen since the 1960s. Japan has always been forthcoming about how the bullet train works, down to the most technical details. The country hosted foreign engineers and sent delegations to advise their contemporaries. So why hasn’t this yielded results in the States? We don’t always have that same “build-to-last” mindset.

After a certain point in the U.S., we have rarely built important stuff fast or that lasts. A few reasons for that:

“Travel speed is not viewed as a priority in the US,” as seen in the gradual slowdown of Amtrak and NYC subway lines

Since the 1970s, “progressives put checks on technocrats who might use government to bulldoze hapless communities,” as seen in the multi-decade reconstruction of Penn Station

Ambiguous power dynamics between developers, government agencies, government leadership, and citizens cause delays, as seen in the reconstruction of Ground Zero

“The United States has become a vetocracy in which intense, well-organized factions litigate projects into stasis”

This sort of friction can be found in any project down to a two-person startup. Building things that last requires brutal re-exploration of which guardrails we put on ourselves and why. Japan had that build-to-last mindset and doubled down on it. Perhaps to a fault.

…But It Has to Pencil

The flip side of building something that lasts is ensuring that it can be self-sufficient. Yes, the Shinkansen is a technological breakthrough that garnered respect from the world. It’s also an utter financial failure.

The Antiplanner, “a blog dedicated to ending government land-use regulation, comprehensive planning, and transportation boondoggles”, reveals the Shinkansen as a whole has never been profitable. By just its tenth year, it was already losing $100M/year.

Antiplanner identifies the following drivers for the losses:

Politicians prevented JNR from shutting down money-losing lines on the outer islands that didn’t need high-speed rail in the first place.

Even on the main island, where 80% of the population lives, politicians demanded that JNR extend the Shinkansen into their neighborhoods, which may not have needed it in the first place. On top of that, these localities didn’t cover the construction, operating, or capital costs. Antiplaner shares,

“Particularly notorious was the Joetsu Shinkansen, which terminates in the city of Niigata on Japan’s northern coast. Being built through mountainous territory, the line cost far more to build than the Tokaido line [the original Tokyo to Osaka line] but carries only one-quarter as many passengers.” He goes on to explain that this was through the campaign of Kakuei Tanaka, an influential member of government who went became the prime minister of Japan… until being convicted for “corruption, accepting bribes, and directing government construction contracts into his prefecture”.

Politicians forced JNR to keep twice as many employees as it needed, racking up unnecessary labor costs.

These sorts of blunders bundled together into an avalanche that Japan has not been able to get out of. This does not take away from the project’s majesty. Just because the Shinkansen hasn’t penciled, doesn’t mean that our ambitious projects can’t. These types of cost overruns can be mitigated. In 2023, we are far more equipped to make data-driven decisions than we were in the 1960s. We can rightsize labor, estimate construction costs, and be diligent about where we’re building and why. The red tape that slows us down can be cut. There are ways to make things pencil. Just make sure you’re doing it towards building a cash cow and not a cost sloth.

Next Stop: Progress

The Shinkansen was made to connect cities, move passengers, and reintroduce the country as a tech powerhouse. The esteem in which the Shinkansen is held globally and its domestic track record proves that it’s done all three. Whether we are building our own bullet train or a newsletter about the bullet train, there are lessons we can absorb. The Shinkansen teaches us to:

Make a Faster Horse Mean Something to have people care about its success

Detach the Cable Car to ensure that the project is completed

Reconsider The Win Condition to prevent guide posts from becoming jail cells

Build-to-Last Mindset takes tremendous sacrifice

But it Has to Pencil - make a cash cow, not a cost sloth

What great thing will you build? What’s your Dream Super-Express?

Keep it Real,

Safi

Thank you to Julianna, Kaley, and Jack for editing!

What’s Next?

Check out other mobility deep dives: Air Taxi company Joby or semi-private plane company Aero.

In honor of The Physicality hitting 500 subs, I am putting together a small dinner to commemorate. If you’re in New York City, send me a note.

Please share this piece with one person you think will find it interesting!