Welcome to the 61 who have entered The Physicality since the last edition! Join the 821 of those who are into learning about the real world here:

I am often lonely.

That isn’t a reflection of the people in my life – they’re incredible. It’s actually because they are incredible that I find myself alone sometimes. The people I hold most dear are traveling the world, building companies, manifesting their imaginations, and even… making families (*gasp*). My solitude is an outcome of my age and the age we have built for ourselves.

This was the precise realization that David Litwak, one of the three co-founders of Maxwell, had before he started a social club to make your new group of friends,

“By 24, you’re no longer going to the same house parties. Someone moved. Someone had kids. Before you know it, you’re taking a stab in the dark for three months trying to get a friend to dinner. Everyone is experiencing this no matter how popular you are.”

In our mid-to-late twenties, we are left to the wind. Previous relationships may no longer serve us. We live with fewer and fewer people. Work takes us to a new city. “Friend groups” naturally fracture – it’s a part of growing up. However, a friend group is your closest community. And when that’s gone, your community is too. My heart ached in my mid-twenties for that unique feeling of a friend group again.

But creating a friend group as an adult feels like an impossible task. TikTok user pjee sums it up hilariously, “I’m in my 20s and I don’t have any friends and I wish I could go to those meetups just to make friends. But I don’t want to make friends with anyone who would go to those types of meetups. Like why don’t you have any friends? What's wrong with you? But at the same time I don’t have friends so they need to make friend meetups for people who wouldn’t normally attend friend meetups.”

Pjee’s TikTok is precisely why I was excited to learn more about Maxwell, the social club that wants to help you build a group of friends. We’ll begin with a brief history, review its many iterations, and explore the community frameworks being experimented with, before ending with how it plans to scale.

Jumping Over the Six-Month Cliff

David and his co-founder Kyle came from different places but in listening to their story, you realize how in tandem they are. David was his college fraternity’s social chair when he met Kyle, who just happened to be starting an unofficial fraternity inside the International House. Both were bringing people together through large gatherings. After college, David continued community-building with a supper club between SF and NYC. A novel idea then, Litwak brought together the most interesting people he could find over regular dinners. When David started to visit Kyle in London, they joined forces to expand the series to a third city.

After two years of co-hosting, they encountered the “six-month cliff.” According to them, after six months, the quality of attendees at their dinner parties bottomed out. They concluded that amazing people have busy schedules and just can’t commit to a set time every week or month.

They realized that a “campus,” a central meeting space, was needed for busy people to reconnect when they could. For example, when a ballerina was off tour or a founder completed their fundraising circuit in SF, they could stop by and continue a great conversation where it left off. Thus, the idea of Maxwell was born.

Plans laid. Locations toured. Letters of intent sent. Full steam ahead. And then… COVID tore through New York City like a paper napkin. Kyle, a New Zealand citizen, had to return to his home country. The project was dead in the water.

Amidst all the chaos, David forgot to take down a job post. Joelle, just finishing her Master’s at the time, applied. David, mighty impressed by her background, informed her that Maxwell was on a hiatus and couldn’t pay her. She wasn’t dissuaded. For the next year, she worked alongside David and Kyle for free. Her contributions to the founding of Maxwell were so instrumental that they named her a third co-founder.

When I asked Joelle why she took the leap of faith with no promise of pay, she said,

“I loved that they were thinking about hospitality in a non-traditional way. I didn’t want to be in traditional real estate myself. People kept telling us, ‘Well, this is how it’s done,’ and we’re like, ‘How it’s done is why most restaurants and bars go under.’ I admired how Kyle and David came to the industry from the outside… I can work with people that I can look up to, that’s why I stuck around.”

The pandemic subsided. Just in time for the ideal location to emerge. It was brick-laden, with 14-foot ceilings tucked away along a cobbled street in Tribeca. A new, private member’s club was born in New York City. And it’s doing a lot of things differently.

A Bar? A Club? No, It’s a Maxwell

Let’s quickly dissipate the imagery you have of a private members club. At ~6,000 square feet, Maxwell is a fraction of Soho House’s 45,000 square foot Meatpacking District location. At its max, it will only have 700 members while SoHo House has on average 4,625 (~185,000 members to share 40 locations globally).

Most shocking is that Maxwell is only open to its 150 current members during the evenings. That’s deliberate. David writes in Community Doesn’t Scale, “[Maxwell] will have one purpose — socializing. You can’t be the spot that people work out of, take dates, power lunches, pool days, happy hours, work out, stay overnight, get a massage…” This social club wants you to socialize! There is an elegance to that – and as we’ll get into shortly, has operational advantages. Precisely how Maxwell facilitates socialization hasn’t been straightforward, however. That has taken many turns.

Version 0: Economies of Community, not Scale

From the jump, Maxwell didn’t want to be like the other girls. They wanted to be a true clubhouse. That required jettisoning standards social clubs have set. The first and most glaring is that Maxwell doesn’t have a restaurant. Or a coworking area. Or a pool. Or any of the amenities we’ve come to expect.

To Maxwell, those amenities are utilities. Most clubs focus on their utility – their features – over outcomes. For example, Soho House’s main page says, “The Houses provide a home for members to eat, drink, relax and have fun in our club spaces, spas, gyms, pools, and screening rooms.” Very little is written about meeting people, deepening relationships, or even socializing. Nothing about amenities inherently generates relationships.

When asked why there is no restaurant at Maxwell, Kyle explains, “Having a restaurant would force you to make decisions around members you wouldn’t otherwise. The restaurant business is low gross margin. You need to turn 200-300 tables over 2.5 times a night to make it work. And that means you’d need about 10,000 people in your catchment area.” Pressures like that change the dynamics of a curated membership club considerably. Not to mention the costs!

In fact, Maxwell took this insight further, wanting to avoid the trap of the “facilities hamster wheel” completely. David writes,

“As Soho House added more [amenities], [they] lost track of the fact that every feature they add requires additional members to support it, and for every additional member, that degrades the community. It degrades the main differentiating factor a private club SHOULD have going for it, which is the people. Every extra member that adds economies of scale reduces the economies of community.”

David hypothesizes that each added amenity forces Soho House to expand their membership base to cover the new costs. Additionally, each new amenity widens the surface area the social club could trip on the service front. Both hypotheses were proven in early 2024. Soho House was blasted for diminishing service quality, long wait times, inattentive staff, and pausing memberships.

Soho House hurts its bottom line by not fostering the clientele. As I wrote in Social Clubs Without Houses,

“Soho House remains a Soso business. For all of its brand power, first-mover advantage, etc., they are plagued by unprofitability even as their membership count swells to the point of [pausing] new memberships. There are certain realities to scaling physical businesses. Between expensive labor and rent, pressure is ratcheted up for social clubs. There are no off days or off-peak times. It’s just an expensive proposition. There is a literal ceiling to how much you can squeeze margins, reduce costs, and raise prices before the house topples.”

So if we know that amenities are not the way, why do most social clubs over-index on utility? Because community is hard. David says,

“It requires personal vigilance. There’s a flight to safety with utility. People will always want a restaurant or a bar. It’s scary for the club to hang their hat on curation. It’s scary to say ‘I think you two should meet each other.’”

This isn’t a condemnation of Soho House. I enjoy Dumbo House’s patio. I crave summer evenings in the pool. I am not above the amenities of the social club pioneer. It's just that Soho House lost the plot once they moved away from intentional community building. It gave Maxwell the opening to try something different.

Version 1: Individual Freedoms Over All

It’s Not an NFT Club

I met David during the depths of the combination pandemic-crypto bull market. At the time, I was obsessed with real-world web3 applications and heard Maxwell’s membership cards would be NFTs. Yes, I am also tired of hearing about them. But given that’s where my relationship started with Maxwell, let’s just blow the NFT thing wide open so we can heal and move on.

Private clubs operate in one of two ways. Soho House and Frats collect “dues” annually or monthly. Others, like golf clubs, offer you an ownership share of the club – an “equity bond.” With this bond, you vote on club decisions and can say that you “own the place.” These bonds can be sold. You can make or lose money off the bond based on its going rate.

In Maxwell’s case, find and replace “bond” in the above paragraph with “NFT.” Same concept, just that the equity bond would be captured on the blockchain. Unsurprisingly, they were pigeonholed for it.

Just like a country club doesn’t focus on how it uses an equity membership, the NFT component of Maxwell was never supposed to be the focal point. Now, Maxwell offers three tiers of equity memberships and one non-equity membership. David reports that the former are built as NFTs but have not even been put on the blockchain. As some guy who is part of a country club would say, “The whole thing was a nothing burger.”

No, You Don’t Have to Cook Your Food

Another narrative that took hold was that Maxwell was the social club where you cooked your own food and served your own drinks.

This concept of self-service came from Txokos, the communal cooking clubs throughout Basque Country. In these private enclaves, members cook for each other and share booze lockers that work off an honor system. David asked, in an age where we’re trying to find ouosen family, why wouldn’t you serve each other? There is something couth about the whole arrangement to me. Yet, they were criticized for it.

The team realized they overextended in how many novel concepts they were introducing at one time. For Maxwell to succeed, they had to find the “Goldilocks level of service.” The major concession made was to keep a bartender on staff every night. Instead of members cooking their own meals, they could cater or hire a chef. David stands by the notion that Maxwell is still hospitality if you have to do a few things yourself,

“No one thinks you’re slumming it in a French chateau Airbnb if you happen to be cooking your own eggs. It’s just a different type of luxury.”

Some tough headlines and misunderstandings out of the way, Maxwell was ready to open the floodgates.

Version 2: The Hottest Parties in Town

Many readers likely were introduced to Maxwell from an event: CAA threw their Tony Awards party there. Tommy Hilfiger threw a Fashion Week Brunch with SZA. Watch parties. Debates. New York Fashion Week. Engagement parties. Instantly, Maxwell was hosting events of every form, nearly every night. Thousands of people were passing through the clubhouse a week.

At the time, I found it contradictory that a members club – a space for small groups of people – was often open to outside audiences. This version of Maxwell believed that hosting the hottest parties in town was “the job to be done.” In retrospect, it probably was the right move for exposure, building their event muscle, and generating tons of cash.

However, membership didn’t correlate with all this action. Maxwell wanted to be a members club, not just another party venue. Something was missing. David realized Maxwell was still pitching features – amenities, events, curation – and not the outcome. That was because Maxwell hadn’t yet figured out who they were pitching to and what the ideal outcome for them was. Until now. David outlines,

“If you’re a socially functional person, it’s not that hard for you to make friends. What is phenomenally hard is creating a group of friends. The events themselves were not making a small group of insiders. What people ultimately want is to be on the inside. By being inside, that’s when you feel seen and heard. The higher order pitch is ‘Here is a group of people for you to be a part of.’”

So let’s go inside.

Version 3: Belonging, Not Curation

Maxwell's mission is to help people who have no problem making friends create their friend group.

David asserts, “We’re making an explicit pitch. A group of friends is what you get. This doesn’t have to be your only group of friends but it has to be a group of friends you’re interested in participating in and wanting to be a part of. We weren’t saying the quiet piece out loud. Now we are.”

Maxwell’s mission of creating friend groups parallels what happened with dating apps. Tinder/Hinge were mired in stigma when they first came out. They were perceived to be used by those who couldn’t get dates otherwise. Of course, that has changed. People use dating apps without (much) shame. Maxwell coming out swinging as the social club for friendship is brave. Building friend groups is complicated stuff. So, they put frameworks in place to make it easier. The first of which is their “Four Legs of Community.”

Four Legs of the Community Stool

Maxwell has identified four qualities that every successful community in history has had: campus, curation, contribution, and rituals. Let’s sit on each.

Campus

A campus is a shared space where you expect to see the same people – clubhouse, a church, college campus.

Curation

Then comes curation, the criteria by which people have been vetted: Harvard Club and alma matter. Zero Bond and profession. Italian clubs and bloodline. Curation implies a high chance that “this group” will be “my people.”

Kyle explains the attributes Maxwell looks for in members are, “Warmth, curiosity, and irreverence - not taking yourself too seriously. People will have warmth because they are outgoing and enthusiastic. Curiosity about other people and the world as a proxy for a working mind. Irreverence, you need that. When people feel secure, their attention goes outwards. It doesn’t get in the way of curiosity, warmth and not taking themselves too seriously. The latest value we’ve added is contribution.”

Contribution

Contribution is where Maxwell begins to feel different than what came before it. David writes,

“If you look at any TRUE community, they all require buy-in with more than just your finances — you teach Sunday school, cook Shabbat dinners, and lead bible study. Members of fraternal orgs or ethnic societies are expected to put on events and serve on committees. College campus life is built on student participation in sports teams, Greek life, clubs, and more. But we seem to have lost this understanding that the key to any good community is contribution.”

You don’t have to lift a finger at any of New York’s social clubs I’ve been to. Perhaps that’s what they’ve been missing this whole time – why they may feel shallow. This laser focus on member contribution is woven through Maxwell’s entire history. The NFTs were really about collective ownership. The Txoko tie-in was about service.

Giving back to the group makes you feel invested. Like you’re part of something larger. I look back at my life and never felt closer to the mosque than when I served food during Ramadan or cleaned up after Sunday school graduation. These acts of service were how I showed my appreciation for the group. Maxwell allowing their members to do the same is special. It makes a ton of sense that you must invest your time, arguably more important than money, in a club to become a part of it.

Rituals

The last aspect of Maxwell’s community stack is rituals. Other communities have Shabbat dinners, homecoming, and Sunday service. At Maxwell, they have nine-person Monday and Tuesday night dinners (both cooked and catered) along with a monthly Family Dinner where members cook for each other.

These intimate gatherings serve as an integration function for newcomers to build cohorts of friends. Long-time member Peter Niehaus states, “Those curated dinners are my favorite aspect of the club. They are the most impactful.” What worked for David and Kyle before – bringing people together over food – is making Maxwell work now. These weekly rituals are buttressed by eight to 10 big annual parties and club retreats.

All Together Now

Any one of the four legs of a stool by itself is a utility. A campus is just a series of buildings (dining hall, library, common area). A curated dinner is great but it’s not community if you never see those people again. At the same time, when utilities are smashed together, they cancel out. David illustrates, “A coworking space has events starting at five but their members work till seven. So you have utilities – workspace and programming – clashing with each other. Which annoys members who want one utility over another at that time.”

Maxwell thinks they cracked the code in a way their peers have not. The formula is,

“Curation repeated over time with ritual in a campus with people bought in via contribution adds up to community.”

On top of this formula, they built a system to facilitate friendship.

The Maxwell Friendship Funnel

When it comes to creating community, David admits that Greek life gets a lot right. They have refined the process of turning strangers into friends through selection, who you’re attracting; And integrating, how you get them to know one another. David explains,

“Your selection process should align with your integration process. The selection process at a fraternity is ‘Who do I want to get drunk with regularly?’ That’s because the integration process is getting drunk with these guys a lot.”

Maxwell has honed in on selecting, “Socially functional nerds. We’re the intellectual discussion types. That’s what matters to us. Once we decided this, everything fell into place. The interviews, the reasons people were joining, everything.”

Their selection criteria matched their integration process, “Our integration process is nine-person dinners so our selection process was ‘Do I want to be at a nine-person dinner with this person for three hours?’ In 20 minutes, if they haven’t said anything worth going off a tangent on, then they’re probably not a fit.”

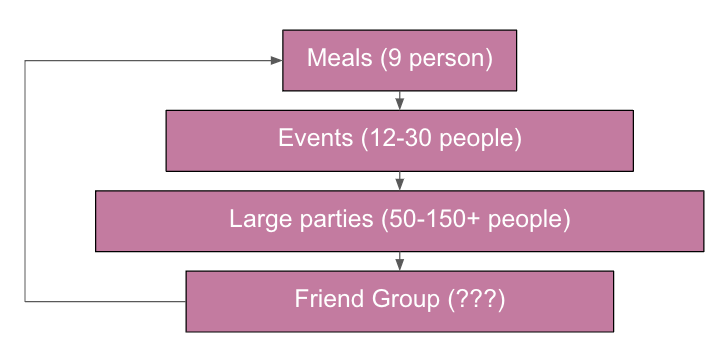

“Integration” at Maxwell takes a few forms. The core events are intimate meals from Sunday through Tuesday. These dinners rapidly integrate you within the club, the culture, and customs. If you attend all three meals in your first week, you have met and re-met somewhere between eight to 24 people.

Claudia, a new member of Maxwell, joined shortly after moving to New York City last July. She decided to join because,

“When David told me that they chose people on ‘we think we would want them at a 9-person dinner?’ I was like OMG. When I was growing up, I had family friends over. For us, a four-hour-long dinner was the ideal evening.”

The intro dinners seem to be working. At her first dinner, Claudia spent time discussing hot political takes. Claudia shared a contrarian one and was surprised at the outcome,

“Even if they weren’t aligned with my hot take, the people were still willing to get to know me. A woman came up to me after saying, ‘I found your take so compelling I had to get to know you.’ I made one of my best friends in New York.”

After these dinners, you attend one of the many events – watch parties, salons, debates, etc. – during the week where you see familiar faces along with new members. By the weekend’s “mansion party,” you’ve seen a dozen members you’ve bonded with over the week. Over time, as you get to know the club and the club gets to know you, you get hand-picked to join and helps events based on your interests.

This process is repeated until you are close to 50 people. David proclaims, “Our goal is to stitch that group of 50 people together. That’s when it starts to feel like home.” This is the system that Maxwell designed to create a group of friends. I can appreciate this roadmap. That sort of process flow is necessary for us New Yorkers. Jordan Stacey, the host of the Voyeurism podcast, stated, “We are separated from community because community disrupts routine, and routine is heavily necessitated in late-stage capitalism. When you’re working 40 hours a week, you save your community for the weekend, for Friday night drinks and Saturday morning brunch. That is the only consistent access to community you have.” Maxwell’s friendship funnel makes a routine of community that we haven’t seen since school, places of worship, and Greek life. This allows for more enriching and multivariate relationships.

Scaling the System, Not the Entity

Each iteration of Maxwell stress-tested an aspect of what the club wants to be. Each turn took one of the variables to the extreme and then pared it back. They established the right mix of member freedoms in v1, the muscle memory of throwing big parties in v2, and are now fine-tuning the member-to-member connection.

Maxwell is templatizing how to form adult friend groups in the technological age. Yet, we know “belonging” stops at a certain limit. Jamie Snedden, co-founder of social club series Groundfloor in California says, “Humanity’s circles have always been local. The solutions that pull from the whole world are quite unnatural. For people to feel a sense of belonging, they have to belong to something small.”

And small is Maxwell’s plan. After 1.5 years of operations, there are only 150 members. This is deliberate. Joelle states, “We are taking membership growth slow. Our community is small. If we add on someone that is just an “okay” fit, it is risking the entire product, which is the community.”

Indeed, the religious center, the community center, the town square, and the piazza all forced people into proximity. David estimates that the membership of its Tribeca location will stay between 600-700 people. That doesn’t mean that Maxwell’s aspirations end at its doorstep. David shares,

“Scaling is important to us. We want to bring this to as many people as possible. We look to churches and frats as ways to deputize. Christianity has scaled communities like franchises. Fraternities scale but each chapter of it is different. We will scale the Maxwell system, not the entity.”

David is taking a tech-forward approach to a traditionally physical problem. The team’s idea is to create a “vertically integrated community hospitality company.” Say that five times fast. They want to:

Templatize everything needed to open and operate a social club: construction, design, operational playbook.

Offer tech that combines events, membership programming, media and internal ops.

Remove pitfalls for new social clubs by making the “unsexy” parts of the business like liability insurance, employment contracts, and equity bonds etc. easier to navigate.

The combination of these things will, according to David’s vision, “Create the machine that spits out individual members clubs, not a coalition of affiliated membership clubs. Local spots that operate independently, with no shared reciprocal memberships between clubs!”

I can’t stop thinking about this. It is an entirely new mental model of how to spread physical community. Regardless of how Maxwell tries to widen its systems of belonging, I commend them for trying to make new friend groups. No massive societal change came from us playing it safe. It takes a ton of vulnerability to admit “We want a group of friends.” Maxwell is banking on that vulnerability to become the social club where you belong, not just where you clout chase.

I asked Claudia, the recent Maxwell newcomer, if she’s made a friend group these last few months. She responds emphatically,

“Yes. A bunch of genuine people who want to be genuine friends. In a place like NYC where it’s easy to get swept away, this is a very grounding place.”

Apply to Maxwell here or learn more here.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Thank you for reading. I know it’s been a while! I have been busy growing Joust and Thursday Labs.

What’s next?

Like what you read? Please like and leave a comment. It helps! Consider subscribing.

Consider sharing this with someone who would benefit from Maxwell.

If you’re a company interested in a deep dive, drop me an email. I only write about one company a quarter now and go DEEP. You can read about my journalism policy here.

Great write up, and mirrors a lot of what we're working on over at www.thesfcommons.com. The tension between coworking and socializing is one of the hottest ones right now.

Great writeup! Big fan of Maxwell and the community they're cultivating.