Welcome to the 18 who entered The Physicality since the last edition! Join the 688 of those who are into learning about the real world here:

I’m a chronic Instagram scroller. Some may say I’m “too online.” In my defense, sometimes the algorithm just hits. But I don’t have to scroll long to stumble upon the new genre of “social club”: Aesthetic. Enticing. People tumbling under a disco ball. Dinner with a C-list Brooklyn celebrity at an art show. A cacophony of mid-twenties socialites playing board games in a dimly lit room. Page after page of real people having real fun in the real world. I must know where it is. I must be a part of it.

I find out that there is no singular location for this club… or that one… or that one. Instead, these social clubs – some you apply to and others you don't – move around the city. The “distributed social club” is an entirely new experiment in the art of gathering. I always just assumed that to be a “real” social club you had to be in a permanent location. But the groups I’ve spoken to for today’s edition are revealing that view is archaic. What can I say? I just got that boomer in me.

After inadvertently starting a distributed social club of my own, I wanted to understand the merits of this model and balance it with the potential drawbacks. To do that, I gathered the perspectives of three distributed clubs and two new takes on the “standing” social club model – one in New York City and the other in California.

What to expect:

The Social Clubs Without Houses

Green Tile Social Club

Junto Club

Parlor Social

The Merits of the Model

The Challenges

The New Social House… is a Social House?

Maxwell

Groundfloor

Engage With the World

The Social Clubs Without Houses

For those who grew up on the sharing economy, this burgeoning model makes tremendous sense. Just as Airbnb proved with individual living rooms, there are pockets of space everywhere that can generate additional value if activated properly. These distributed social clubs leverage that same core idea, filling the back rooms of restaurants, flooding hotel lobbies, and using coffee shops after hours. I found three of these new social clubs for us to explore further.

Green Tile Social Club

What began as an Instagram story seeking mahjong friends spiraled into Green Tile Social Club (GTSC), a mahjong event series that introduces the game to a new generation. Held throughout New York City, GTSC boasts 200+ participants per event, with multiple events a month that usually last about four hours. Jo Xu, one of the four co-founders who I interviewed for this piece, updated me that they’ve hosted about 55 events for 10,000 guests to date.

Junto Club

Andrew Yeung is known for throwing all sorts of networking events from thousand-person gatherings at the Williamsburg Hotel to intimate founder dinners. As he sought to make the right connections after moving to New York City, he realized that “cool spots” would be the draw for the people he wanted to meet. So, Andrew went out to build partnerships with venues all over the city. In just a few years, he has now hosted over 30,000 people. A subset of his more curated events are through his Junto Club umbrella. Although there is an application process, the Junto Club is more a professional event series than a formal social club. Shockingly, Yeung doesn’t charge his guests a dime. He tells me, “You shouldn’t have to buy your way into building meaningful relationships.” He wished he had an accessible way to meet peers and mentors when he started in New York, so he created it for others.

Parlor Social

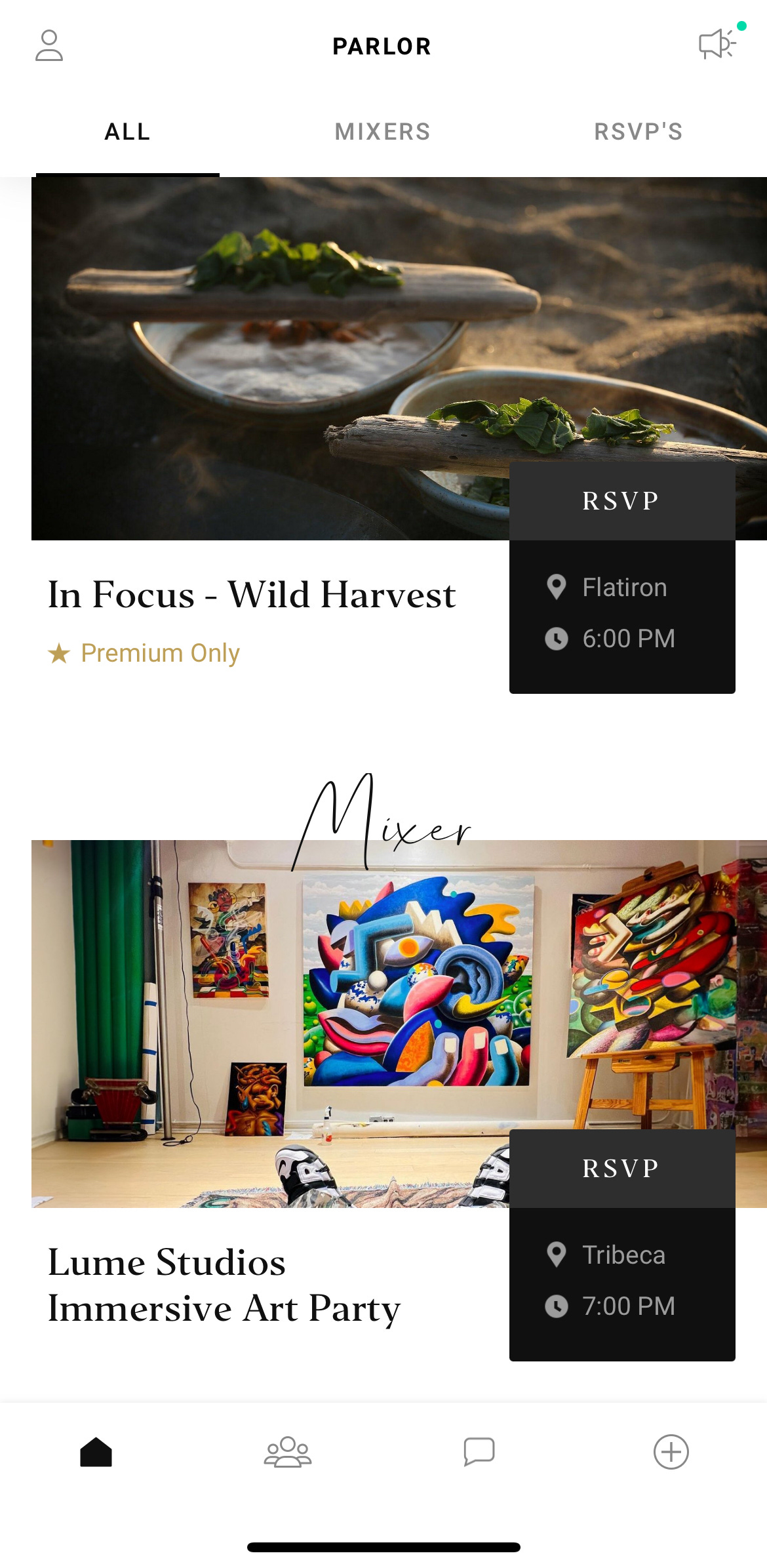

Parlor Social is the most “tech-forward” of the three distributed clubs we gathered today. The core of their experience is an app that continually curates real-life events for you as you interact with their world. It begins by gathering information about your social preferences, the age group you want to meet, the types of events you want to be invited to, and your reasons for joining (networking, dating, friends). As you attend comedy shows, dinner parties, and art showings, it will recommend future events and nudge you toward people the algo thinks you’ll get along with. In an interview with Manual, co-founder Frederick Ghartey said, “We want to be a one-stop solution for your social life”. With close to 10,000 members and an astronomical ~68,000 applications in review, Parlor may be both the largest distributed social club and the largest repository of social life data… ever? I sat down with co-founders Frederick and Jan for this edition.

The Merits of the Model

There is a reason the distributed model is taking off – it just makes sense. The benefits are aplenty but I narrowed it down to three: venue variety, community flexibility, and potentially superior economics.

Venue Variety

In my head, the “pop-up” model was always a means to an end. You use events to garner enough of a community that you can then convert to a permanent membership. So, I was surprised to hear that was never the master plan for Green Tile. They started in public parks before creating a network of AAPI venue partners. The necessity of rotating through different venues allowed them to create relationships with culturally relevant spaces that helped Green Tile Social Club thrive.

In turn, distributed concepts allow members to provide business to venues they may not have gone to otherwise. This symbiotic relationship between culturally relevant locations that need more clientele and GTSC bringing that clientele is a win-win. What others may see as a forcing function is precisely what allows this club to work so well.

For Parlor, there is a freedom in the sheer breadth of events they can offer members that can only come when the walls of your club extend as far as the city limits. Their thesis is that venue variety = programming novelty = longer membership tenure over a traditional club. Constantly shifting around events they offer and where they do it keeps their audience engaged. Venue variety keeps things interesting for the club owners and the members they serve.

Community Flexibility

The distributed approach allows for community variety as well. Parlor Social benefits from casting a wide net across age groups, intentions, and interests. At any time, they can laser-focus on one subset of the community and build out experiences for them. Even with its “exclusive” and “upscale” veneer, Parlor is sneakingly inclusive compared to its classic counterparts.

Keeping Junto Club floating allowed Andrew the flexibility to change the community's makeup based on demand. For example, he noticed startup founders tending to mingle with other founders over other guests. He immediately arranged a founder dinner series to foster this Junto Club cohort. When your social club isn’t confined to a clubhouse setting, you don’t have to make just one social club, you can make countless.

Potentially Superior Economics

Soho House remains a Soso business (yes, that will be the title of my impending Soho House deep dive). For all of its brand power, first-mover advantage, etc., it can’t seem to get its shit together. They are plagued by persistent unprofitability even as their membership count swells to the point of having to pause new memberships. There are certain realities to scaling physical businesses.

Between expensive labor and rent, it makes sense that 80% of New York City’s restaurants close every five years. That pressure is ratcheted up for standing social clubs. Soho House runs essentially a high-quality hotel restaurant… but for the entire day. There are no off days or off-peak times. It’s just an expensive proposition. There is a literal ceiling to how much you can squeeze margins, reduce costs, and raise prices before the house topples.

Distributed clubs don’t face the same challenges. After founding both classic and distributed clubs, the Parlor team concludes that distributed is, “just the better model. You’re not paying rent. [In the standing model], you spent a lot of time on A/C, making sure the floors are clean, etc. We are more interested in what makes a good social life.” Without the pressures of hefty fixed costs or maintaining an on-site staff, Parlor can focus on delivering interesting and varied experiences.

Without a set overhead, distributed models lend themselves to being considerably more affordable for their members. Right now, Parlor is charging $40/month for full access. Green Tile’s ticket prices are modest and often include food and drinks. As mentioned before, Junto isn’t charging at all. When you don’t have to think about making rent, you don’t need to think about nickel and dime-ing your members. Instead, you can put all your efforts toward providing continuous novelty and a high standard of hospitality.

The Challenges

I want to be all-in on the distributed model. Heck, I’m banking on it being a thing. But I can’t help but notice its flaws. I made sure to explore them with this edition’s subjects. The same two popped up across all three clubs: inconsistent hospitality standards and establishing true community.

Inconsistent Hospitality Standards

Soho House’s customer service is suffering because their key venues are bloated. There are just too many orders for the staff to meet them in a timely fashion. With service standards falling, there is a mismatch between what members are paying for and what they’re receiving. Green Tile’s Jo says, “We’ve seen with Soho House, it’s hard to maintain every detail every day. We only have to maintain it for three hours.” The pressure to deliver a stellar experience is still on, of course. But it seems more sustainable when you only have to keep it up for a few hours a week.

However, Jo admits, “The key challenge of this pop model is that we are subject to the whimsy of other businesses.” Without controlling the physical space, there are unique operational challenges and unpredictability. Last week, one of their core venue partners closed. She isn’t worried, “There is beauty in [the unpredictability] because “community” is already interconnected. There’s a cause and effect.” She says the team is certain they will find a new venue partner that also “moves with their vibe”.

Hospitality is about maintaining a sense of consistency. When you are “borrowing” someone else’s space, you’re at the mercy of that venue’s capabilities. Several things can go wrong that you don’t have direct control over. To mitigate venue risk, each social club handles things a bit differently.

Parlor leans on its app to collect data on how each of its venue partners performs. That data dictates whether or not that particular partner remains in their rotation.

Junto focuses on working with the right hospitality partners that align with their vision. Reaching this point took incredible discernment, trial, and error. To mitigate partner risk, Yeung has built a cache of relationships so that if one doesn’t work out, he can walk across the street. With the partners he remains with, he always looks to provide additional value back to them. He shares an example of helping one of his key hotel relationships with executive hiring.

Similarly, before GTSC gets into a partnership, they ensure there is an energetic alignment. Jo tells me, ”Can they intuit being a third space naturally? By the time we are getting to the production cycle, those burdens are already lifted.” For her, maintaining hospitality standards within a distributed club comes down to ensuring more than logistics.

Establishing True ‘Community’

A social club built for everyone is a social club built for no one. Each concept covered above is made for quantity. To me, I assumed these endeavors would create many shallow relationships. Can the distributed model create a genuine community at a thousand-person-plus scale?

Andrew of Junto clarifies that it isn’t his intention to create “community” at his large-scale events. He reserves that focus for his more niche gatherings. In those, he follows a strict protocol to ensure each guest meets and has the contact information of one another. Now, he is working on an app that may bridge the gap between offline gatherings and online connectivity. He thinks “tech could be the answer here.” Of course, Parlor Social agrees with him.

The Parlor team admits that establishing intimate connection is, “a work in progress.” But they are leveraging technology to create consistency, “At Parlor, before you go to an event, you get connected to people and see what events they went to and what events they will go to in the future. This slowly nudges you along to create a relationship. We make sure there are core people who are invited to the same events. If we have the right technology, they will find each other.” It’s certainly a leap of faith in the power of algorithms to bring us together. As someone whose application just got accepted, I will report back on how it goes.

The New Social House… is a Social House?

Between Soho House flailing financially in tandem with the rise of these distributed clubs, it seems like the standing model’s time has passed. That hasn’t stopped New York City’s Maxwell and SF/LA’s Groundfloor from trying their darndest to establish a “House” with healthy business fundamentals.

David Litwak, co-founder of Maxwell, explained that the distributed model is merely an evolution of the “retreat” movement from a few years ago. These retreats were meant to, in his words, “find your community by leaving your community.” Notable examples include Summit, “a community made up of the world’s most diverse makers and holistic leaders [that] gather people to effect positive change in the world” or MaiTai, a kiteboarding-focused retreat for the tech/VC crowd that was the “the beginnings of a new TED.” Some of these concepts are still active while others have fully retreated from the world.

Given that retreats are costly and time-consuming, it opened the door for the event-series wave we’re in now. David sums it up as, “a two-hour retreat instead of a two-day one.” While Litwak supports both movements, he doesn’t believe that either can create deep or long-standing communities. These series-type arrangements are too heavy of an ask for the highest quality of people’s time. The people you really want to meet are coveted. They are not always free to show up at the same time, every time. What they’re missing, in his mind, is a campus – like Maxwell.

He tells me, “Every community is a stool with three legs. Curation. Events. Campus”. He makes a parallel to Harvard. The rigorous application process curates the people. Events like “Welcome Week” allow you to meet them. A campus provides that connective tissue to meet again without scheduling. “The campus does the work for you behind the scenes. You are all members here. You can exist and friends will find you.” According to him, the campus model is the soil needed for deep relationships to grow in the socially arid New York City.

Jamie Snedden of Groundfloor, a social club with four locations in SF and LA agrees, “A friendship takes time, continual touch points, repetition, and commonality. You need to meet ten-plus times over a few weeks, and almost always see them in the same place. Humanity’s circles have always been very small and very local. The solutions that can pull from the whole world are quite unnatural.” To Jamie, we shouldn’t fight our tendency to congregate around a central location. It’s how we’ve always built community.

The religious center, the community center, the town square, the piazza all forced people into proximity. Snedden asserts that ‘small’ is the only form factor that works, “For people to feel a sense of belonging, they have to belong to something small. You can’t take a shortcut. If shortcuts worked, then we wouldn’t have this [loneliness] problem in the first place.” Something to consider.

By their nature, standing social clubs are exclusionary. Given space limitations, you need to cull the crowd in some dimension. Historically, this was done by only allowing in people who could either afford it and/or a certain race and/or gender. So how do you execute the physical social club in a way that meaningfully attacks the loneliness epidemic? Jamie claims what we need is, “coffee shop-level density in a big city.” To him, that means many 5000 square feet clubhouses that can fit up to 500 people. In this way, more people can access intimate spaces where they will come across the same people repeatedly.

Maxwell is right with them. In Community Doesn’t Scale, Litwak calculates that a social club should be capped, “No community should be more than 600 people. The minute you let people who are part of another city’s community drop in, you are becoming a facility, not a community. If you only have 600 members, you don’t need a lot of space. Definitely not the 25,000–100,000 sq ft+ properties many private clubs have.” To someone who has seen dozens of third spaces come and go, this all still sounds costly.

Both clubs have their own thesis on improving the economics of a standing social club. Maxwell’s is to remove the restaurant, the biggest line item for a club altogether. Members bring their own food and have a liquor locker. This lowers labor and maintenance costs considerably.

Jamie, on the other hand, optimized the existing standing model. He created a repeatable system to build Groundfloor’s locations quickly and with “positive unit economics.” Translation: opening and operating each location profitably. He reports that his latest build-out only took a mere four weeks — unheard of in the present day. It’s a narrative violation. Quicker build times mean less chance for construction cost creep. More importantly, it means members pay dues faster. With a first principles approach, maybe there is a way to make the standing social club work for more of us.

Engage with the World

Derek Thompson writes in the piece, Why Americans Suddenly Stopped Hanging Out, “Something’s changed in the past few decades. After the 1970s, American dynamism declined. Americans moved less from place to place. They stopped showing up at their churches and temples. America’s social metabolism was slowing down.”

Distributed social clubs are a symptom of the times. It goes deeper than Jo’s seemingly one-word summary of ”post-covid-get-back-in-real-life, digital-community-does-not-suffice.” The multivariate, multi-mood, multi-vibe nature of the distributed model lends itself to a society accustomed to ingesting everything in a swipe-style format. Jo concludes that in NYC, “Your social needs change day-by-day, sometimes hour-by-hour. So that choice is appealing.” We are down bad with ADHD.

Litwak feels adamant that “the mental model of what ‘community’ is has atrophied in American society. Before, ‘investing in community’ was meant to be done over years, not weeks.” You don’t have to look further than dating apps to see how we have shifted our value system in relationship building. While I’m surrounded by loving couples who came from the apps, trusting all of your relationships to come from the algorithm may be folly.

But there aren’t enough third spaces to fill the gap! Loneliness is an infrastructure issue. Zoning laws keep us apart. Our cities aren’t laid out to bring us together. Economic conditions require spaces to close, giving people fewer reasons to get out. This was felt slowly, and then after the pandemic, all at once.

The stark truth is that we don’t know how to replace what was here before. Something broke in us along the way. Yet, I’m proud we are trying. I can see and hear and feel our desire to reinvigorate our social metabolism. I recognize the excruciating effort these clubs are making to create bonds. Both distributed and standing social clubs are clawing and scrapping to save us. Regardless of which model we opt into, it requires a huge ask of us: Go engage with the world.

Keep it real,

Safi

What’s Next

Go sign up for Green Tile, Junto Club, and Parlor Social. If you let me know you did, maybe I can get you off the wait lists.

If you want in on fancy game nights, fill out the Joust Interest Form so I can invite you to a fancy game night.

Send this piece to your bestest friend you want to see more of.

Like and…

Great article! I like the opportunity to expand the social club scene and it's need for physical space...plays well into my theory of the future of office buildings.