PadSplit: Helping Others is Just Good Business

Crafty Capitalism to Solve the Housing Shortage

HNY! Welcome to The Physicality, where the new 2024 official tagline is: “A newsletter breaking down companies building the real world.” Real world = real estate, mobility, and travel. If that sounds interesting to you, join the 520 others that think so as well:

Today’s piece is eligible for commission. Please read The Physicality’s Deep Dive Program to learn more.

Y’all know I never do public math. But this seems like an easy enough calculation:

We need ~7 million housing units (rooms) to solve homelessness in America.

Let’s say each unit is 600 sq ft, the size of a studio apartment.

(7 million rooms) X (600 sq ft) = ~4 billion square feet to solve homelessness.

The natural reaction is, “Wow, that’s a lot of housing we need to build!!11!11!”

But… we have already built 255 billion sq ft of housing, much of which is underutilized. We would just need to reallocate a minuscule 1.7% of housing already made to end this issue.

That calculation is the backbone of PadSplit, which empowers landlords to turn properties into affordable co-living arrangements. Similar to Airbnb, they provide a marketplace for landlords and renters. But instead of facilitating short-term rentals, PadSplit rents out medium-term, fully furnished rooms. It’s opened my mind to using crafty capitalism to solve the hardest problems. To learn more, I sat down with PadSplit Founder and CEO Atticus LeBlanc.

Today’s build:

Decline of Rooming Houses

PadSplit, the anywhere SRO

Most Need, Most Headaches

Doing Good by Doing Well

Decline of Rooming Houses

Government affordable housing programs have failed us. It doesn’t matter if we are discussing low-income housing, project-based Section 8, housing subsidies, or rent assistance – we have the highest rate of homelessness ever.

There are entire dissertations on why it’s getting worse, most of which come down to bad policies. One of those bad policies relevant to today’s subject is when the most affordable unsubsidized rental housing option was systematically removed from the housing stock without alternatives.

Rooming houses, a.k.a. single-room occupancy housing or SROs, are sort of like dorm rooms. They are small, furnished, private rooms that share bathrooms and kitchens with other residents. They used to be everywhere in New York City and other major metropolises. You know, the good ol’ days when working minimum wage could afford a roof over your head.

SROs were not public housing. These were private enterprises that allowed for a cashier, construction worker, or bartender to take residence near their place of work – even if it was in an expensive neighborhood. These were many families' first homes when landing in Manhattan while they searched or saved up for more permanent accommodations. As of 2013, the median rent for one of a few rare units was $450 - $705 / month.

You probably haven’t heard of SROs because this once widely accessible housing option was bludgeoned away by public policies and private interests. Forgive me for quoting Wikipedia, but this was just written too beautifully (with sources),

“Reformers used moral codes, building codes, fire codes, zoning, planning committees and inspections to limit or remove SRO hotels.”

From the 1890s to the 1960s, SROs were labeled as “urban blight” for spreading disease, crime, and (*clutches pearls*) homosexuality. If that campaign didn’t work, the legal angle was used: They aren’t safe or up to code, etc. Hundreds of thousands of these units were removed from New York, San Francisco, and Chicago without any alternative for those who needed them. It’s a tremendous policy failure that we are still feeling the ramifications of today. CUNY Law review asserts,

“The [New York] City’s decimation of SRO housing has amplified the ongoing housing crisis, constricting the low-income housing market and contributing to the ballooning homelessness problem. The overall effect on poor and working-class residents has been tragic.”

If the affordable argument doesn’t stir you, perhaps a market demand one will. 28% of Americans live alone, yet only 1% of housing is studios. I am sure anyone living in NYC/SF would welcome more options.

What’s old is new again. New York City Mayor Eric Adams recently proposed changes allowing SROs to return to the city. Yet, converting existing housing to SROs or building entirely new ones requires significant capital investment and governmental oversight.

If only someone enabled SROs to work anywhere for a fraction of the cost, using existing housing stock.

Enter PadSplit, the anywhere SRO

We are getting wise to the idea of getting more out of what we already have. Since the pandemic, office-to-residential conversions have been heavily toted as the solve for urban affordability problems. But all this excitement only yielded 3,575 units last year. What if we applied that “use what we already have” thinking to existing residences instead?

For PadSplit, there is no “housing shortage,” just a housing misallocation. There are rental homes, vacation homes, underutilized rooms in existing homes, and second homes that are making less cash than they could be. PadSplit’s premise is straightforward: If you, Mrs. Landlord, increase the number of liveable spaces in your property… you can generate more rent! In turn, this makes each room more affordable for renters.

On top of that, cash flow is more stable because PadSplit members must stay for a minimum of 31 days and also pay by the week. Right now, the average stay is 8.7 months. This all just makes proper cents.

PadSplit refers to this model as “co-living” – but not in the way that Common, WeLive, and others did it. Like those companies, PadSplit bundles rent, utilities,Wi-Fi, and furniture into one monthly payment. However, they did away with yoga classes and wine nights. Instead, the put tools in place, like inter-house messaging, to allow a community to form naturally. Atticus shared that houses often have regular dinners. In a rare occurrence, one house even took a vacation to Miami together.

Like Airbnb is an infrastructure layer in the short-term vacation rental market, PadSplit is the same for the SRO one. In fact, many current PadSplit hosts used to be Airbnb hosts but switched over when they found it to be more lucrative.

PadSplit sets the housing standards for the landlords, which include both governmental requirements and PadSplit-specific ones. For example, “all homes must include utilities, furniture, and internet”. They also provide owners data to inform their operations, like what sorts of rooms have the most tenure, what houses are bringing in the most cash flow, etc.

Currently, PadSplit takes 12% of all revenue. After February 1, 2024, PadSplit will take the first 10 days of revenue and then 8% of each day thereafter.

On the tenant side, PadSplit members are, on average, 35 years old and earn a median income of $30,000 per year. To support them, PadSplit focuses on doing three things right:

Providing Housing Quickly

Pick a home, get approved in minutes, and move in within 48 hours. They achieve this speed by excluding any deposits or requiring a minimum credit score. Even without the typical landlord “protections,” they still boast a 97% collections rate.

Their underwriting system is only what’s necessary: identify verification, proven income, criminal background check, eviction history, and a short survey to determine if they have “shared values” with the PadSplit community. It’s important to note that landlords may have their own approval criteria and are free to reject whomever they want.

Payments Process

PadSplit’s app accepts all forms of payment (debit, prepaid debit, credit, ACH), even without a bank. Members can use CashApp and Zelle via debit payment.

Trust

Every housing arrangement comes down to trust between landlord and tenant — and, more importantly, between tenants. PadSplit provides a roommate rating system, so you have transparency on who you’re living with before choosing a stay.

A benefit of not holding any hard contract or deposit is that it makes it easy to get out if needed. At any time, if a resident feels uncomfortable, they can instantly transfer to any open unit on the platform. Anyone breaking the rules will lose their coveted access to PadSplit. Just like with Airbnb, eviction, police action, etc., are in the landlord’s wheelhouse.

PadSplit is providing value on both sides of the marketplace. By taking a first principles approach to identifying the specific needs of those that both supply and live in affordable housing, they have been able to create a superior rental product.

It’s a win for landlords who want more and more stable cash flow. It’s a win for tenants who want affordable, safe and furnished accomodations. It’s a win for the government who needs to solve the housing crisis. It’s a win for taxpayers who won’t get pulled into building net new housing. So why isn’t it everywhere?

Most Need, Most Headaches

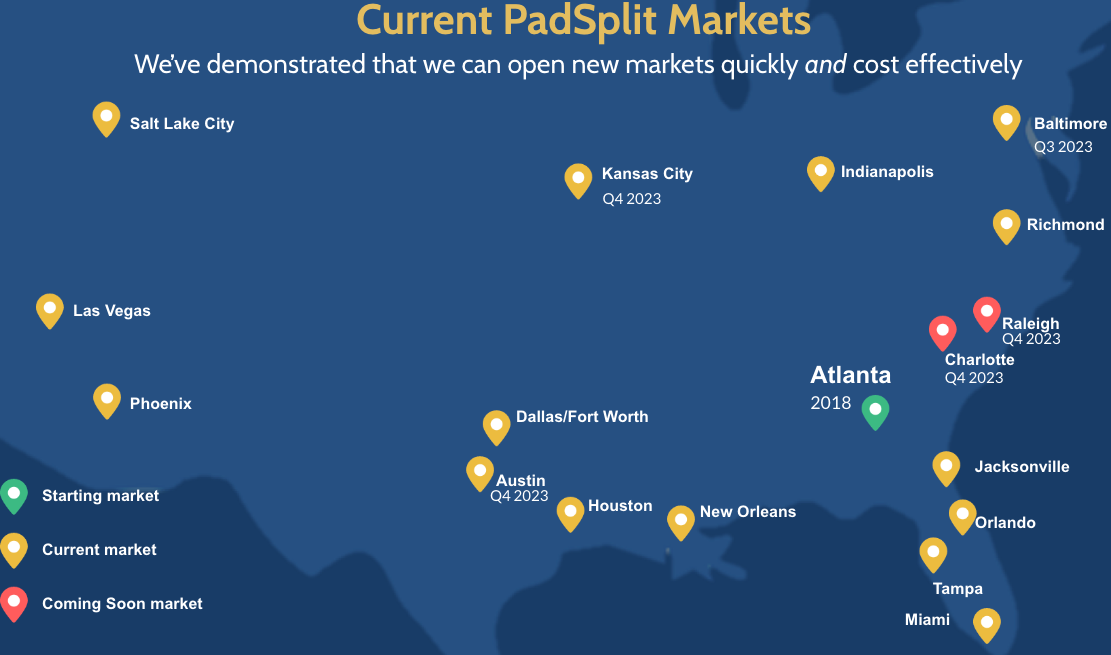

PadSplit has housed more than 22,000 residents across the following markets:

You’ll notice that the two cities most referenced when discussing the entire American unaffordability crisis – New York City and San Francisco – are not there. Atticus asserts that PadSplit eagerly wants to help with housing issues in those markets. However, the powers that be make it a relatively less attractive proposition. For starters, in New York specifically, zoning law prevents more than four unrelated people from sharing a residence. Fewer tenants per property means less revenue for landlords.

Atticus notes that the markets with the most need generally have the strongest tenant protections. Directionally, this is a good thing. But on second look, they are occasionally nonsense. Take the case of the lady who overstayed her welcome in a California Airbnb… for 570 days. This was the second time she did this, btw.

In response to the potentially high costs and time investment for eviction, landlords have historically mitigated tenant risk by introducing high barriers to renting: credit requirements, security deposits, personal references, and, in NYC’s case – requiring that your annual income be 40 times more than monthly rent. These burdensome risk mitigators have made the affordability problem even worse.

PadSplit, like any other good business, operates where it’s feasible. These markets tend to have more balanced tenant protections and regulatory clarity. Take Houston, where homelessness has plummeted by 60% in 12 years. This was largely due to the government making it easy for developers to create housing. We need to revisit the guardrails that are stacked so high that it’s become a jail cell, forcing the housing crisis to metastasize.

PadSplit aims to hit a million rooms by 2030. That seems like an enormous leap in six years, given where they are today. Atticus shares that their footprint grew 5% month-over-month in the second half of 2023, putting them on track for 900,000 rooms by year-end 2030.

It’s not like there isn’t a need. New York or San Francisco aside, there are plenty of cities that would do well to have more PadSplit. Desert News reports that between 2020 and 2022, “homelessness in Phoenix rose by 22%; in Austin by 26%; and in Sacramento by a staggering 68%.”

Who knew doing good would be so hard?

Doing Good by Doing Well

Given that housing is a basic human right, there is an ongoing debate on who should be allowed to provide affordable housing. Limited to the government? Private companies? Altruistic nonprofits?

I find this argument to be pointless as long as quality, humane affordable housing remains out of reach for this country. I imagine the millions of Americans who are either on the street or living in sub-par conditions would rather be housed privately than suffer publicly.

And the argument is a moot point. For years, the government has tried to incentivize private developers to help with the crisis. Just one of the incentives in New York City allows buildings with less than 300 units with a certain amount of affordable ones to receive a 100% real estate tax exemption for three years during construction and for 25 years after that. Although that’s a staggering amount of tax savings, the program clearly hasn’t solved the issue. Because of the tenant dynamics laid out before, affordable housing still doesn’t pencil.

PadSplit made affordable housing a superior business proposition. This has allowed for more residents to live in humane spaces with the utilities and furnishings they need for a stable life. What’s remarkable is that PadSplit becomes more lucrative the more people it helps. It’s not charity. It’s Capitalism. They are serving a segment of the market that badly needs improvement. By creating a superior and differentiated product for their customers, PadSplit could help millions of Americans – and become more successful because of it.

The more PadSplit wins, the less necessary it becomes. Atticus isn’t worried. He tells me,

“If we can be the lowest-cost provider of housing, we will always have a business.”

Helping others and providing shareholder value at the same time? Now, that’s just good business.

Want to help others and make money doing it?

Thanks for reading! Thank you to Julianna, Jack, and Kaley for editing.

Keep it real,

Safi

Really interesting, thank you for the deep dive! This feels like it could solve a lot of problems, but could it make people more lonely? We're more atomised than ever AND still glorify the indivdual, despite it making us pretty miserable. But you're so right on homelessness and even more than that: being single is a financial luxury nowadays and people are forced to give up their independence just so they can afford a roof over their head. I'm torn.. are PadSplit planning any community building activities?